Simple

Linear Regression

R Packages

- rcistats

- tidyverse

Palmer Penguins Data

Variables of Interest

flipper_len: Flipper Length in millimetersbody_mass: Body mass in grams

Modeling Relationships

Modeling Relationships

A Simple Model

Estimating Models

Linear Model

Prediction

Explaining Variation

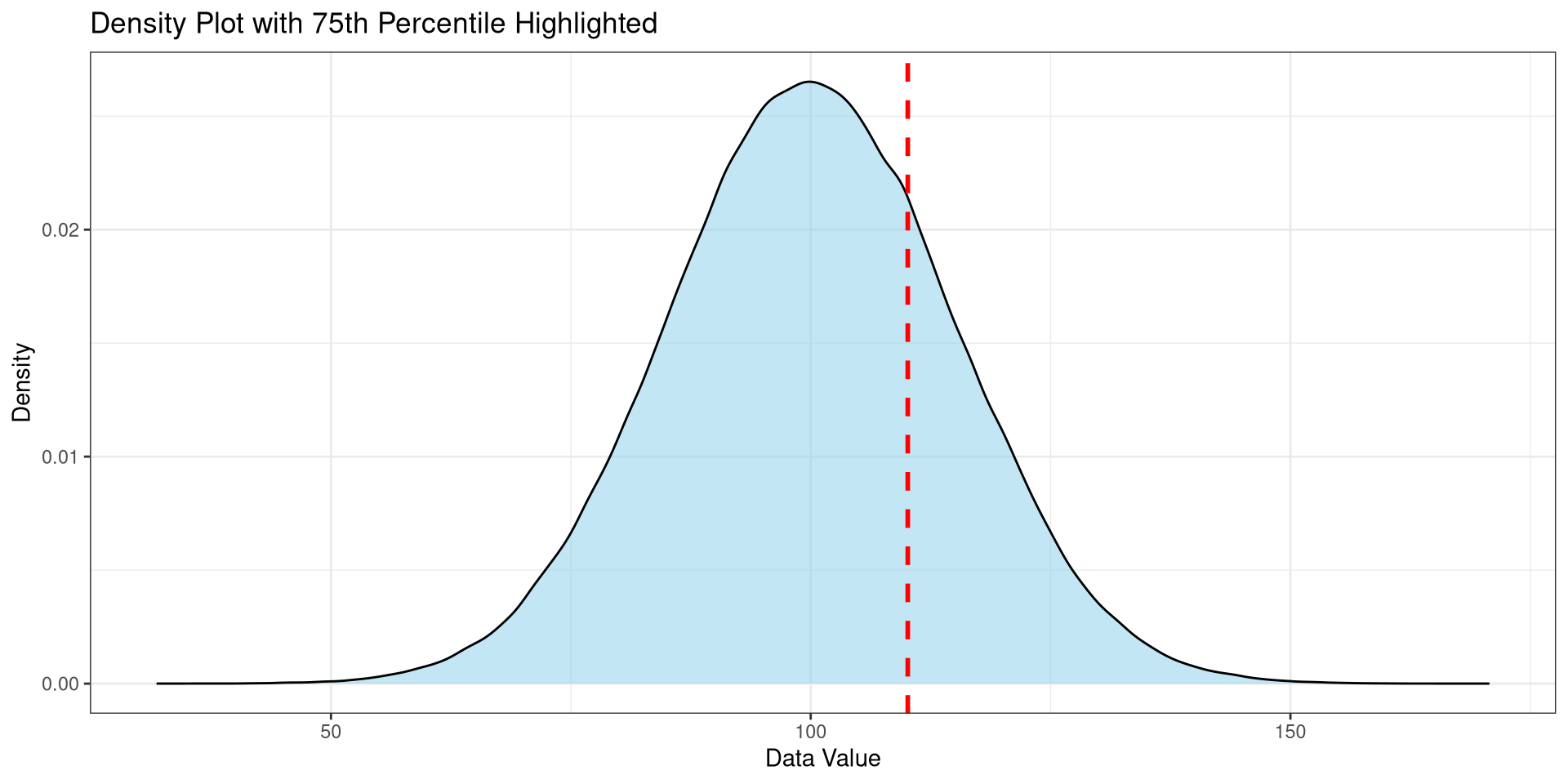

This is the process where we try to reduce the variation with the use of other variables.

Can be thought of as getting it less wrong when taking an educated guess.

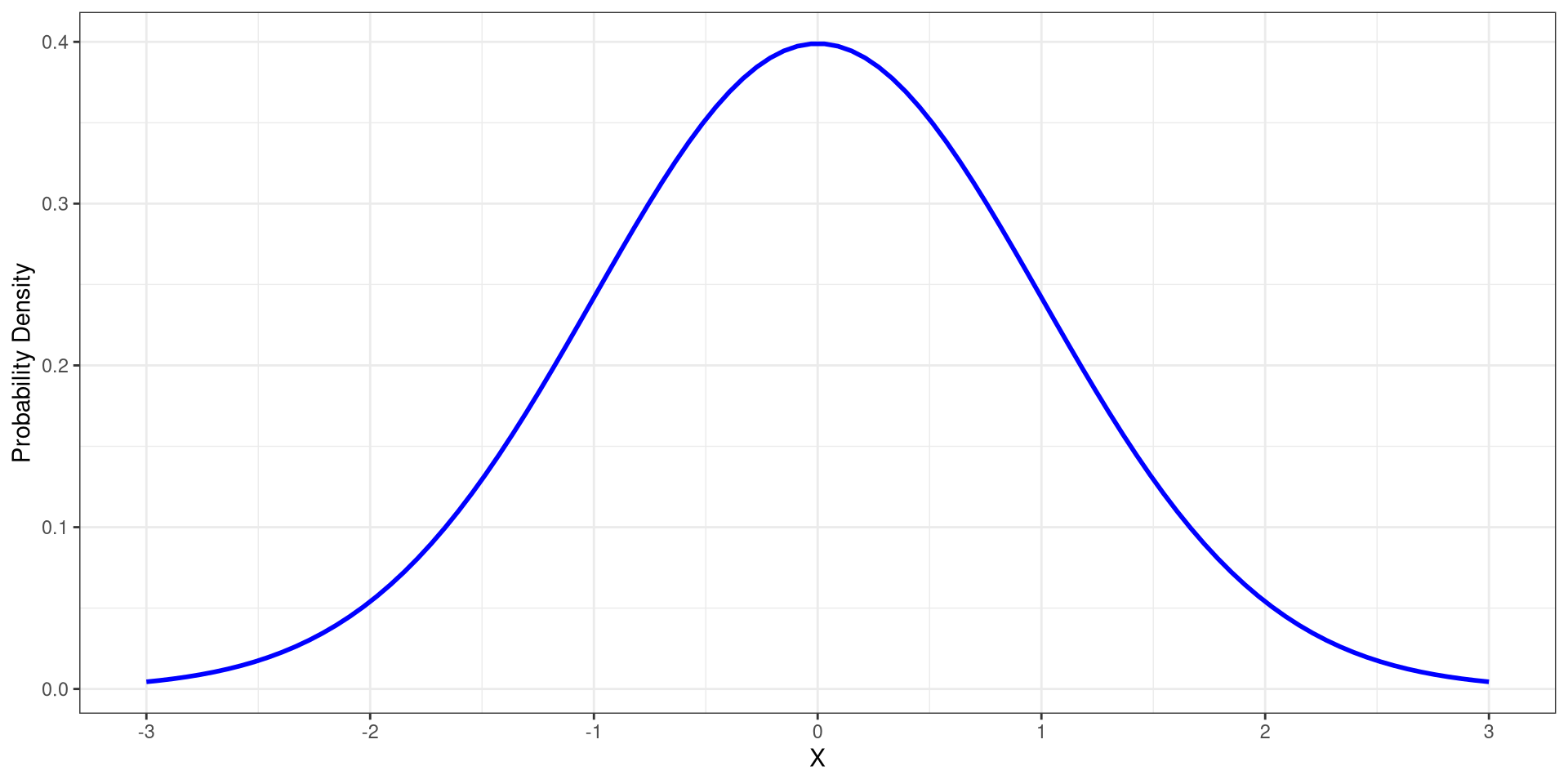

Modeling Variation

Modeling Variation with \(\bar X\)

Modeling with a Numerical Variable

Modeling with a Numerical Variable

A Simple Model

Modeling Relationships

A Simple Model

Estimating Models

Linear Model

Prediction

Generated Model

\[ Y \sim DGP_1 \]

A Simple Model

A Simple Model

\[ Y = \_\_\_ + error \]

The Simple Generated Model

\[ Y = \beta_0 + \varepsilon \]

\[ \varepsilon \sim DGP_2 \]

\(DGP_2\) is not the same as the \(DGP_1\), it is transformed due \(\beta_0\). Consider this the NULL \(DGP\).

Observing Data

\[ Y = \beta_0 + \varepsilon \]

Estimated Line

\[ \hat Y=\hat\beta_0 \]

Notation

Observed

\[ Y = \beta_0 + \varepsilon \]

Estimated

\[ \hat Y = \hat \beta_0 \]

Estimating Models

Modeling Relationships

A Simple Model

Estimating Models

Linear Model

Prediction

Indexing Data

The data in a data set can be indexed by a number.

#> bill_len bill_dep flipper_len body_mass sex year

#> 1 39.1 18.7 181 3750 male 2007Making the variable body_mass be represented by \(Y\) and flipper_len as \(X\):

\[ Y_1 = 3750 \ \ X_1=181 \]

Indexing Data

\[ Y_i, X_i \]

Data

With the data that we collect from a sample, we hypothesize how the data was generated.

Using a simple model:

\[ Y_i = \beta_0 + \varepsilon_i \]

Estimated Value

\[ \hat Y_i = \hat \beta_0 \]

Estimation

To estimate \(\hat \beta_0\), we minimize the follow function:

\[ \sum^n_{i=1} (Y_i-\hat Y_i)^2 \]

This is known as the sum squared errors, SSE

Residuals

The residuals are known as the observed errors from the data in the model:

\[ r_i = Y_i - \hat Y_i \]

Estimation in R

Y: Name Outcome Variable of Interest in data frameDATADATA: Name of the data frame

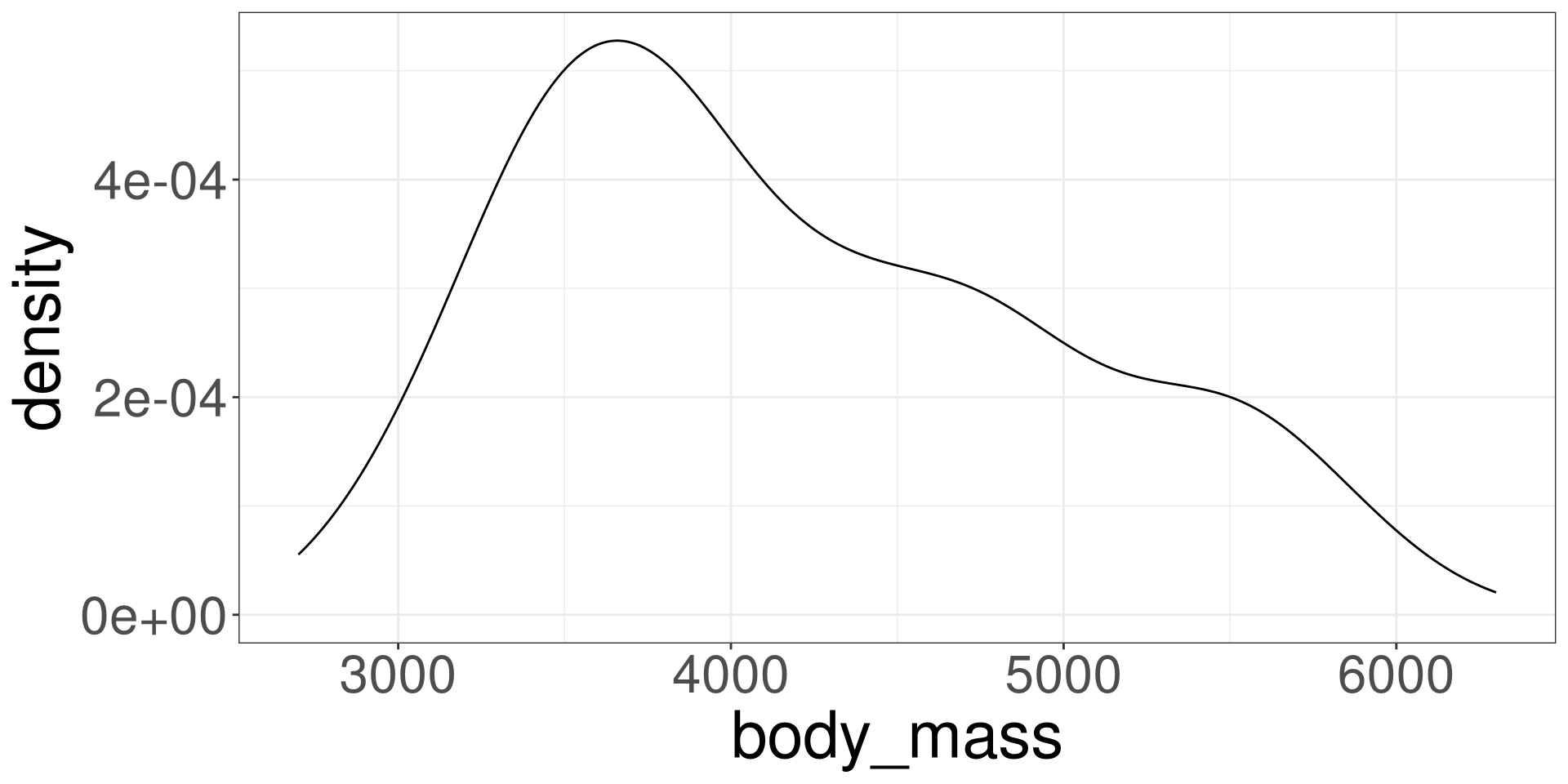

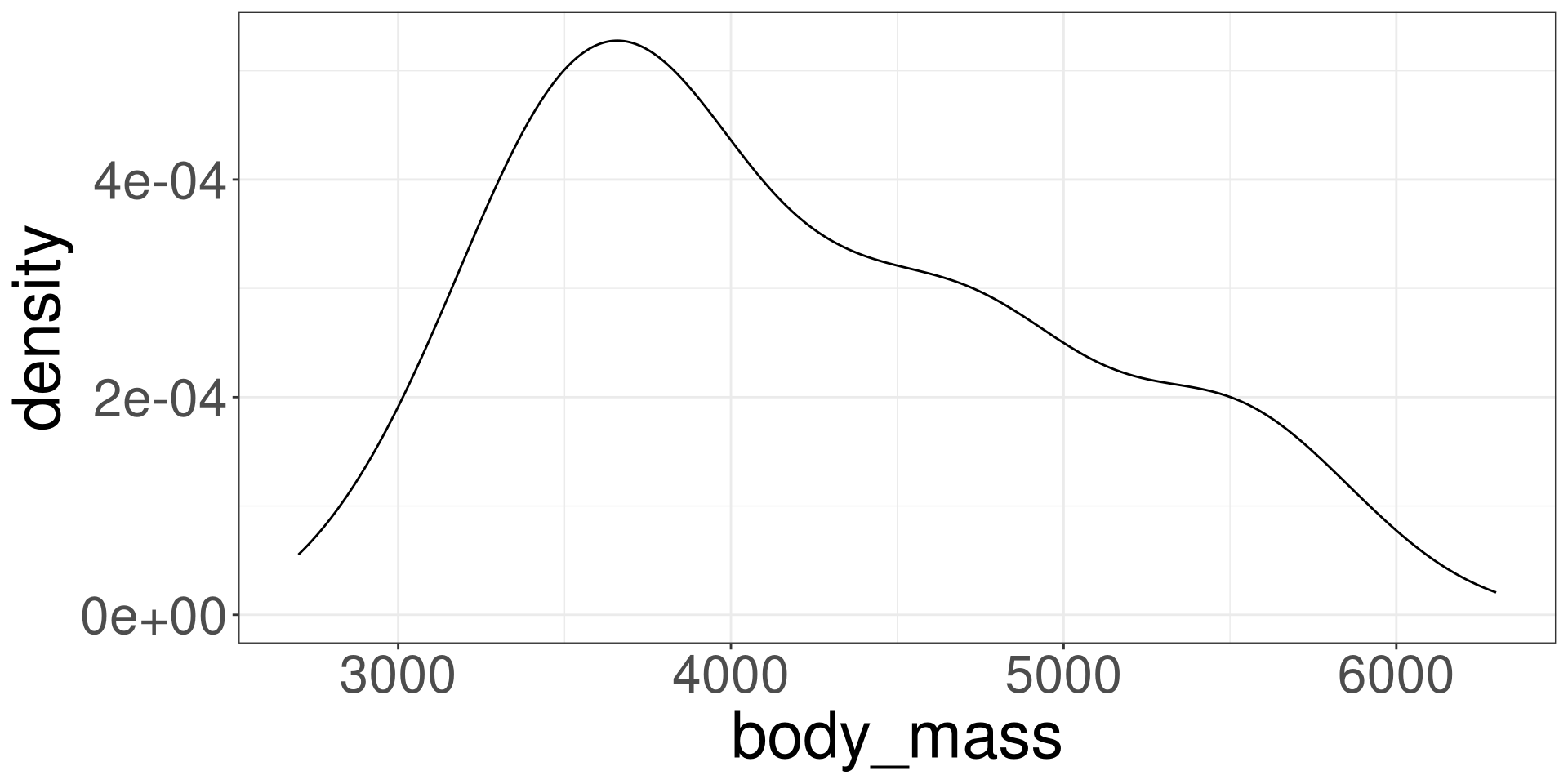

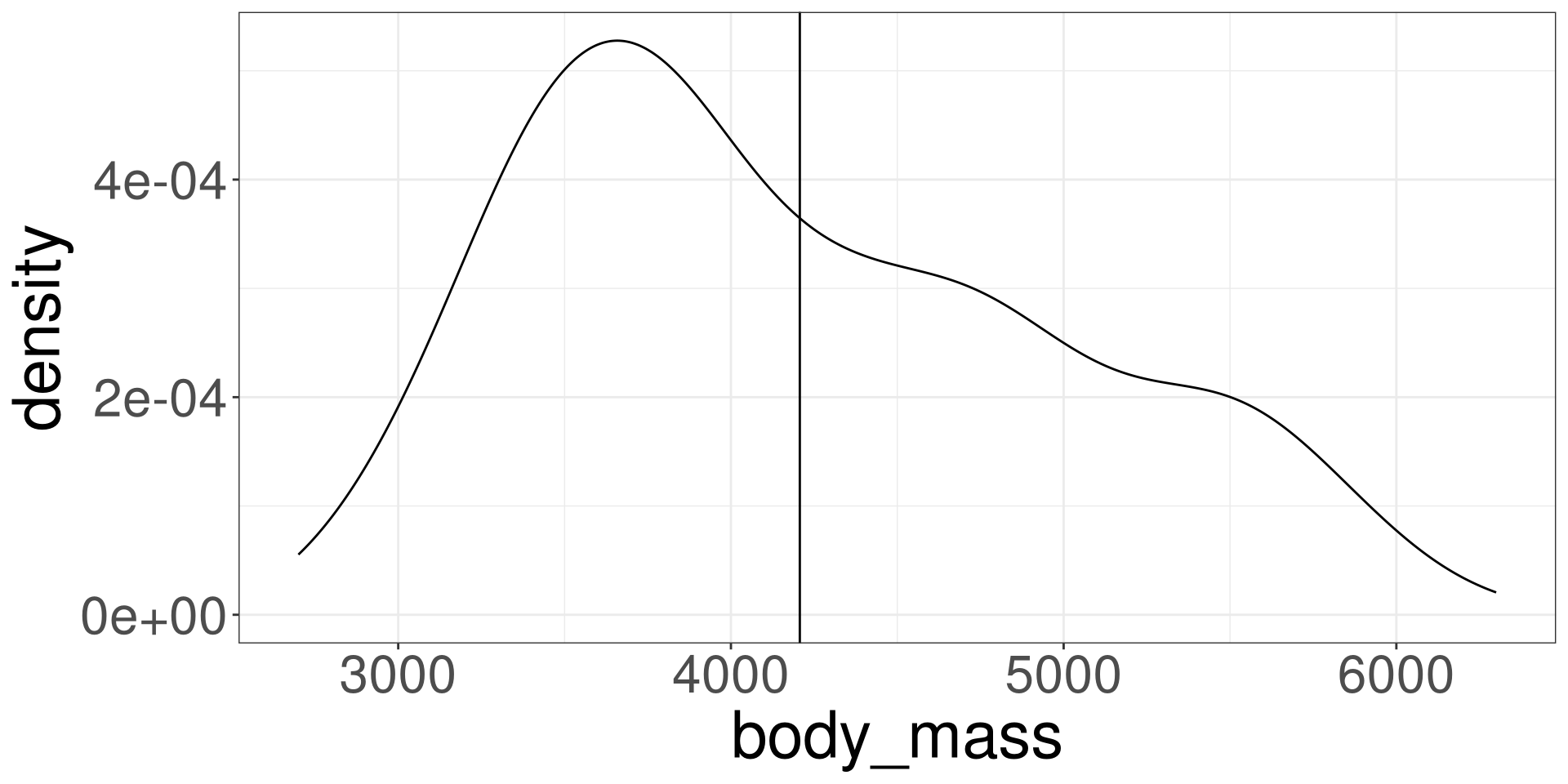

Modeling Body Mass in Penguins

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = body_mass ~ 1, data = penguins)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> (Intercept)

#> 4207\[ \hat Y = 4207 \]

Visualize

Linear Model

Modeling Relationships

A Simple Model

Estimating Models

Linear Model

Prediction

Linear Model

The goal of Statistics is to develop models the have a better explanation of the outcome \(Y\).

In particularly, reduce the sum of squared errors.

By utilizing a bit more of information, \(X\), we can increase the predicting capabilities of the model.

Thus, the linear model is born.

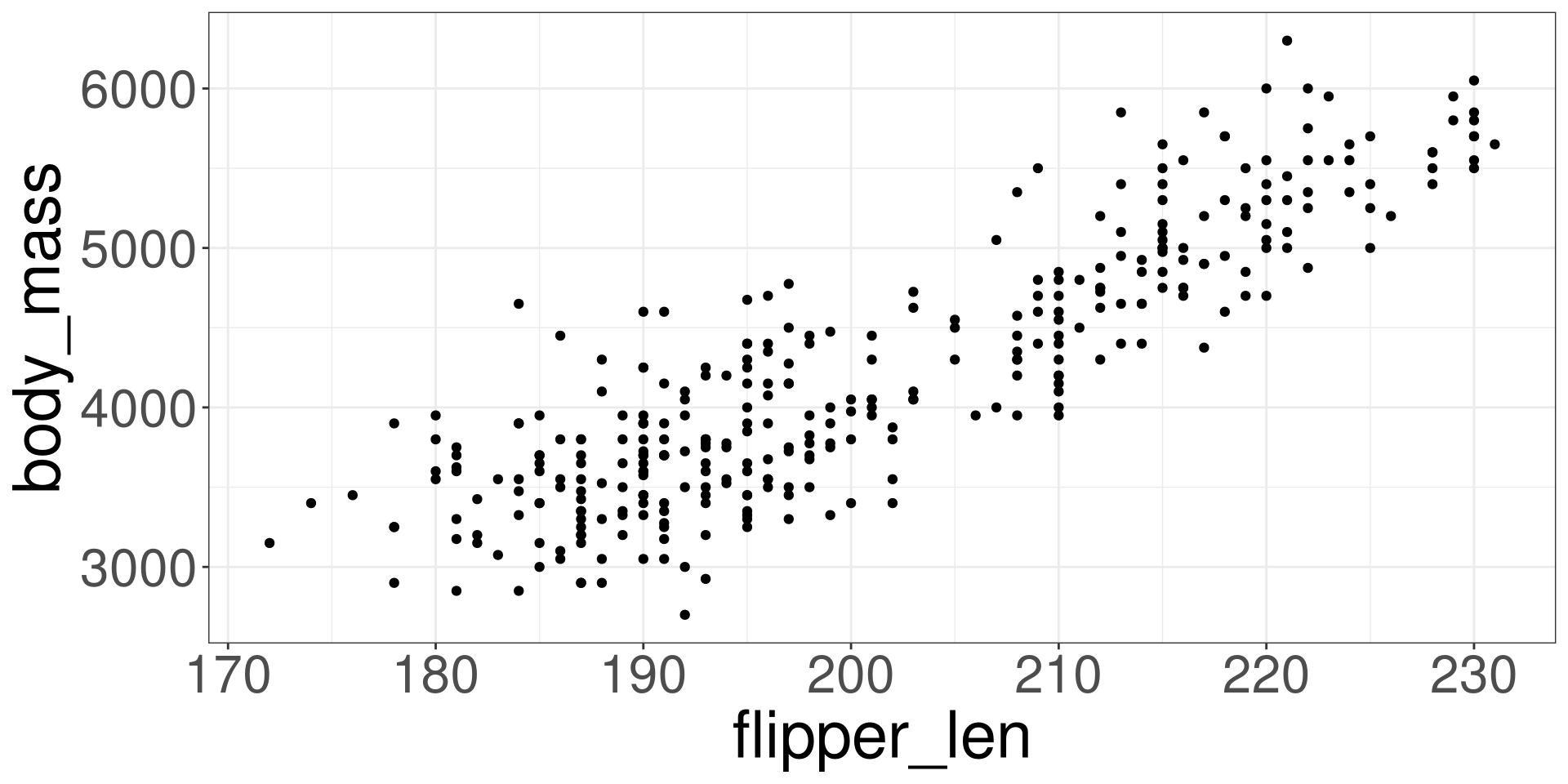

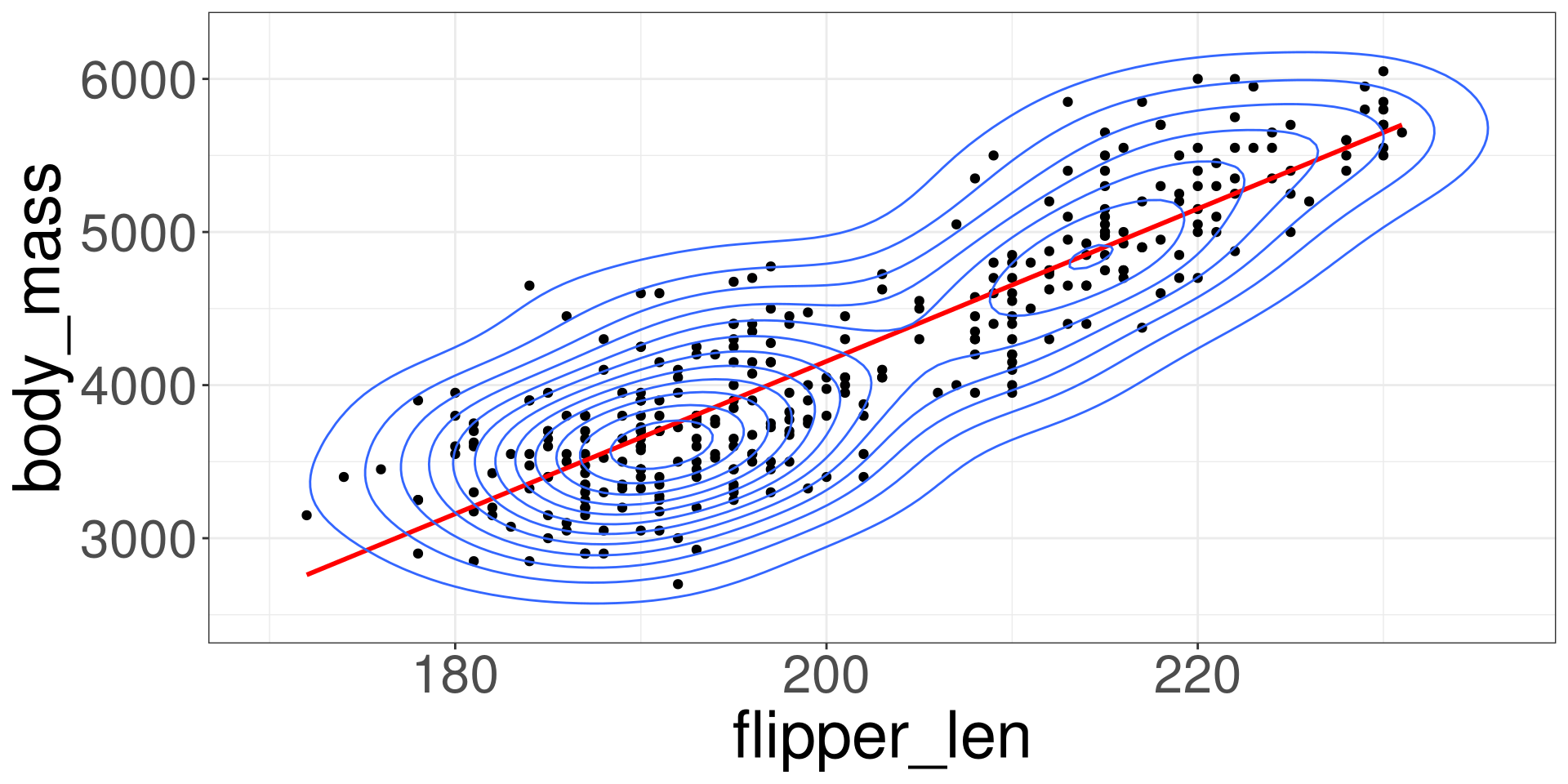

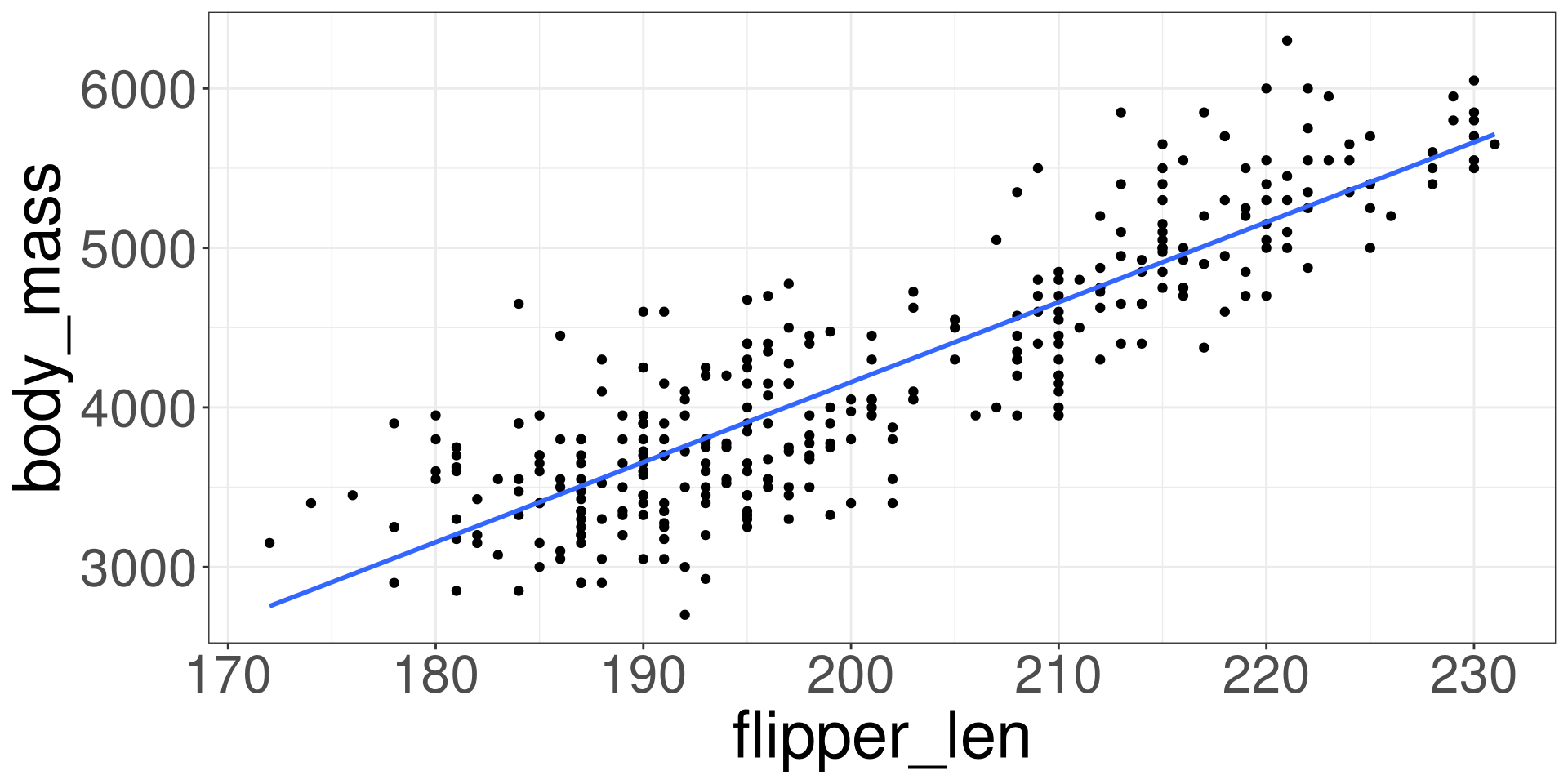

Visualization

Linear Model

\[ Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + \varepsilon \]

\[ \varepsilon \sim DGP_3 \]

Scatter Plot

Imposing a Line

Modelling the Data

\[ Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_i + \varepsilon_i \]

Linear Model

\[ \hat Y_i = \hat \beta_0 + \hat \beta_1 X_i \]

Goal is to obtain numerical values for \(\hat \beta_0\) and \(\hat \beta_1\) that will minimize the SSE.

SSE

\[ \sum^n_{i=1} (Y_i-\hat Y_i)^2 \]

\[ \hat Y_i = \hat \beta_0 + \hat \beta_1 X_i \]

Fitting a Model in R

X: Name Predictor Variable of Interest in data frameDATAY: Name Outcome Variable of Interest in data frameDATADATA: Name of the data frame

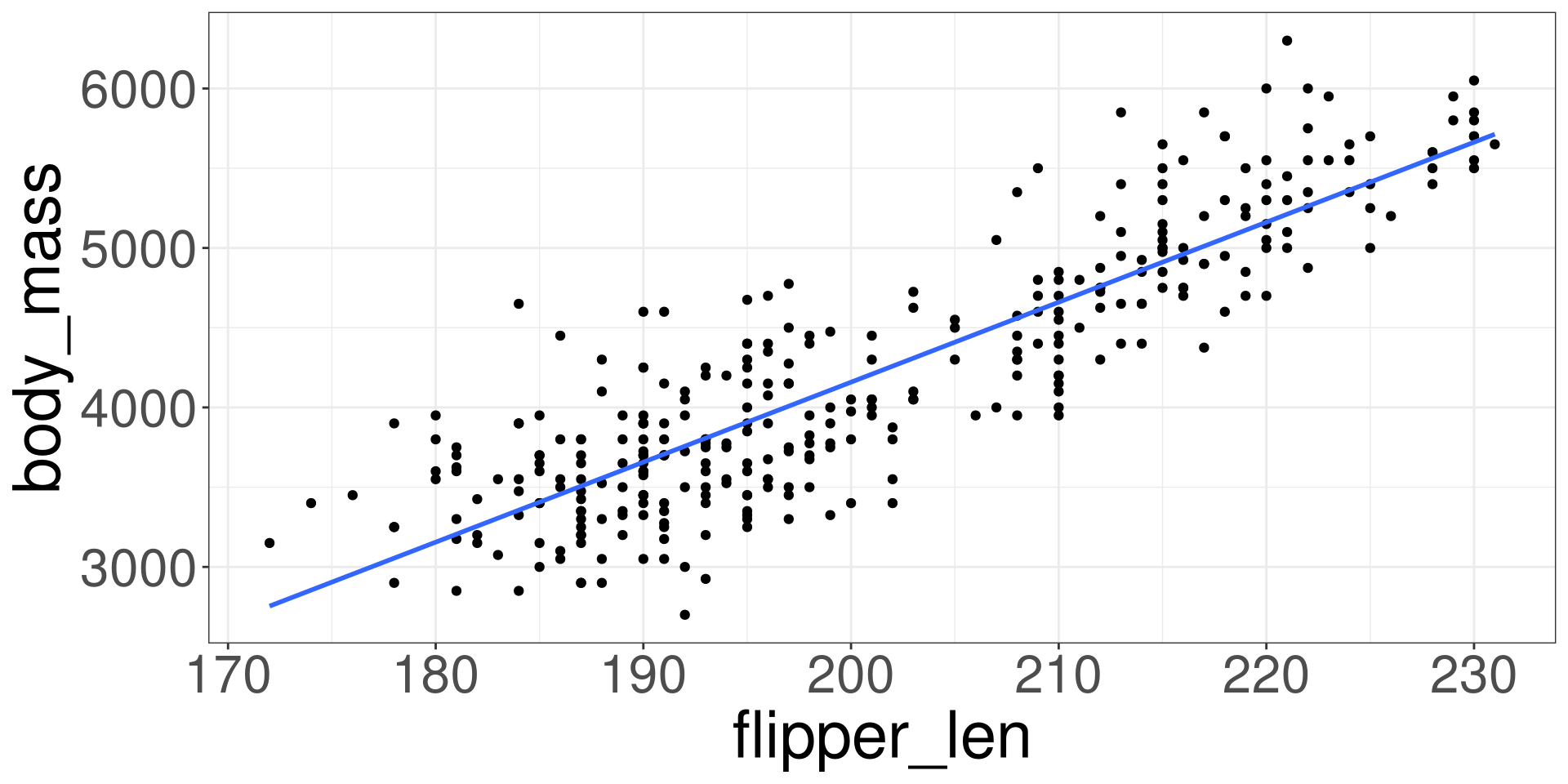

Example

Y: body_mass; X: flipper_len

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = body_mass ~ flipper_len, data = penguins)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> (Intercept) flipper_len

#> -5872.09 50.15\[ \hat Y_i = -5872.09 + 50.15 X_i \]

Interpretation of \(\hat\beta_0\)

The intercept \(\hat \beta_0\) can be interpreted as the base value when \(X\) is set to 0.

Some times the intercept can be interpretable to real world scenarios.

Other times it cannot.

Interpreting Example

\[ \hat Y_i = -5872.09 + 50.15 X_i \]

When flipper length is 0 mm, the body mass is -5872 grams.

Interpretation of \(\hat \beta_1\)

The slope \(\hat \beta_1\) indicates how will y change when x increases by 1 unit.

It will demonstrate if there is, on average, a positive or negative relationship based on the sign provided.

Interpreting Example

\[ \hat Y_i = -5872.09 + 50.15 X_i \]

When flipper length increases by 1 mm, the body mass will increase by an average of 50.15 grams.

Prediction

Modeling Relationships

A Simple Model

Estimating Models

Linear Model

Prediction

Statistical Model

\[ \hat Y = \hat \beta_0 + \hat \beta_1 X \]

- \(X\): Input

- \(\hat Y\): Output

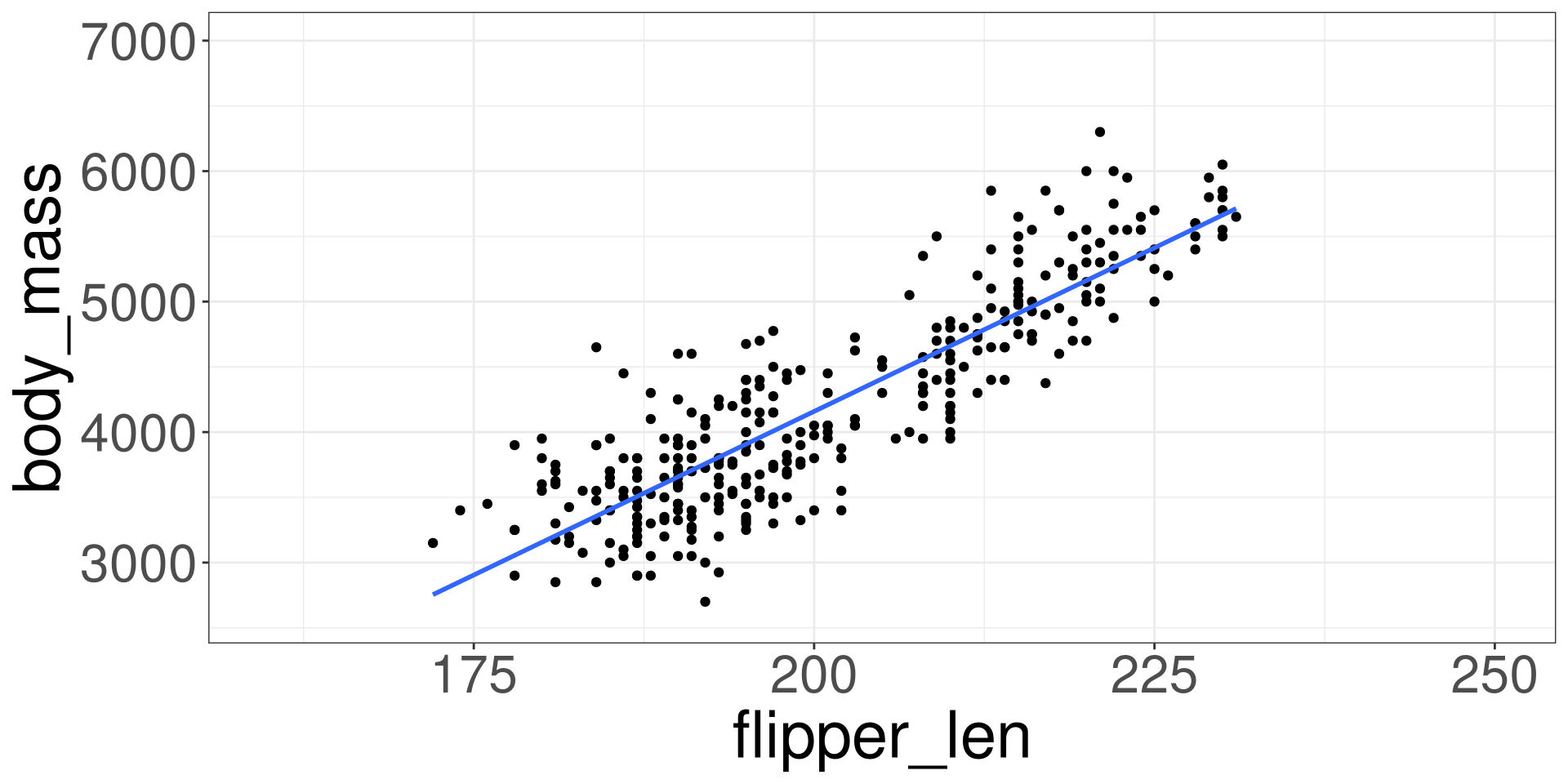

Prediction

Using the equation \(\hat Y\), we can give it a value of \(X\) and then, in return, a value of \(\hat Y\) that predicts the true value \(Y\).

Prediction in R

X: Name Predictor Variable of Interest in data frameDATAY: Name Outcome Variable of Interest in data frameDATADATA: Name of the data frameVAL: Value for the Predictor Variable

Example 1

Predict the body mass for a penguin with a flipper length of 185.

Example 2

Predict the body mass for a penguin with a flipper length of 205.

Interpolation

Interpolation is the process of estimating a value within the range of the observed input data \(X\).

Extrapolation

Extrapolation is the process of estimating a value beyond the range of observed input data \(X\). It’s about venturing into the unknown, using what we know as a guide.

Extrapolation

Code

m201.inqs.info/lectures/5